|

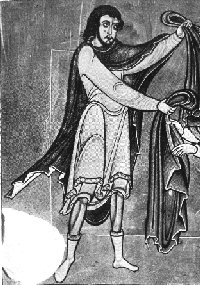

Clothed Seemly and Proper, the Second Part: The late 11th and 12th centuries In the ninth and tenth centuries, clothing in Western Europe followed a fairly basic pattern of layered tunics and half-circle cloaks. The Saxon clothing discussed in the last article was typical of Saxons in both Britain and Europe, as well as being similar to that worn by the Franks. Over the late eleventh and the twelfth centuries, these simple trends were gradually replaced by more exaggerated - and in many ways, less practical - fashions. In Britain, changes in fashion were the result of political changes. The Norman invasion of Britain in 1066 heralded important cultural as well as political changes. The Norman nobility, settling in Britain with grants of formerly Saxon land from William the Conqueror, tended more towards decoration and refinement of fabric than their Saxon counterparts, and as life became more peaceful after the Conquest, these refinements increased. The importance of the Crusades should be noted here; after the First Crusade in 1096, interchange with Oriental cultures exerted considerable influence on European styles in the use of rich and delicate Eastern fabric, as well as certain styles of clothing (e.g. the bliaut and Oriental surcoat). Winchester bible, 1170 At the beginning of the period (mid-eleventh century), both men and women favoured the layered effect of a shorter, wider-sleeved overtunic, worn with a longer, tighter-sleeved under-tunic. Where male Saxon or Frankish tunics were just below knee-length, by the end of the 11th century menís tunics could be almost full-length, at least for formal occasions (Kelly and Schwabe, p. 3). The emphasis thus began to be placed on effect as much as practicality. In womenís clothing, this was taken to extremes with the extravagantly-lengthened sleeves of the overdress. The defining feature of this period in costume, as distinct from Saxon and Frankish styles, is length and fullness! Menís clothingThe outer tunic became much longer, often trailing on the ground; its sleeves also became longer and fuller; and richly-embroidered borders were much in evidence. While the skirts of the tunic were full, the body was often more close-fitting than the Saxon or Frankish version. The toes of shoes became longer and pointed, as well as being more closely fitted to the foot, and the shoes themselves more richly decorated. The mantle was very similar to the Saxon mantle, although longer and fuller - a half-circle with an embroidered border, caught at the shoulder with a heavy, often jewelled clasp. The tunic was now sometimes slit up the front, occasionally as far as the waist (Cunnington, p. 11). Headgear also came into fashion, including a small round cap and various styles of hat.

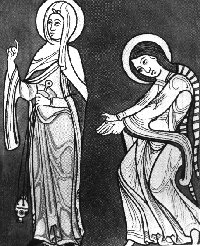

Bury St. Edmunds bible, 1140 Womenís clothingThe lengthening of sleeves and hems seen in the menís costume was taken to amazing extremes by the women; the over-tunic sleeves, lengthened to the wrist, were also widened dramatically below the elbow. (The effect of this was sometimes almost boat-shaped; see illustration). According to some authorities, knots might be tied in the fabric to stop excessively long sleeves from dragging on the ground (Norris, Truman). Hems, too, were lengthened at the back and sides to form a train. Girdles, worn around the hips, were often made from cords knotted at intervals with metal and jewels. (See illustration on first page of this newsletter). Hair was worn in two plaits which were also exaggerated in length with cloth tubes. Over the plaits was worn the veil, held in place with a circlet; the end of the veil could be brought over the shoulders to cover the throat.. Oriental influences saw the development, in the twelfth century, of the bliaut, a highly flattering full-sleeved, voluminous over-dress made from fine, flimsy, pleated fabric (silk, silk crepe or gauze), bound to the torso from just under the bust to below the hips. Another Eastern-inspired garment was the Oriental surcoat, a loose, full, flimsy and transparent over-robe fastened with a brooch (Norris). The half-circular mantle remained in use, although it tended to be lengthened to trail on the floor.

MS illustration, 1120-1150 12th century marble, Chartres. BibliographyPhyllis Cunnington, Costume in Pictures (1961). Dutton Vista. Francis M. Kelly and Randolph Schwabe, A Short History of Costume and Armour (1931). Batesford. Herbert Norris. Costume and Fashion Nevil Truman, Historic Costuming (1936). Pitman Press.

|